The Founders Interview

A conversation with

Luke Lirot

Longtime First Amendment Attorney & Defender

Interview and story by ED Founder Don Waitt

(NOTE: This story appears in the July 2023 issue of ED Magazine.)

S

unday mornings are supposed to be relaxing. Which is what I was trying to do one bright and sunny Florida morning about 15 years ago. I was sitting outside on the lanai, smoking a cigarette, drinking a cup of coffee and reading the newspaper, which people used to do back then.

But then my cell phone rang.

“Hello.”

“Hi Don, it’s Alex.”

Alex was my son Tyler’s girlfriend. Tyler was about 25 at the time.

“What’s up?”

“Tyler’s in jail.”

“Excuse me?”

“He’s in jail.”

My natural assumption, receiving such a call on a Sunday morning, was that my first-born had been arrested for DUI the night before. I said as much to Alex.

“No, it wasn’t for a DUI.”

“What was it for then?”

“Felony assault.”

“Tyler was charged with felony assault?”

“Actually, three counts of felony assault.”

“What the hell. Who did he assault?”

“A police officer.”

“A police officer?”

“Actually, three police officers.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

So much for a relaxing Sunday morning. I asked Alex for more details and then got dressed and drove to the jail for Tyler’s bond hearing.

The next morning, I picked up the phone and did what many adult nightclub owners across the country have also done when faced with a huge problem.

I called Luke Lirot.

* * *

Lirot worked his magic pressing the flesh down at the courthouse and was able to get my son Tyler’s felony assault charges reduced. The fact that Tyler had never been in trouble with the law before, was a homeowner, and openly acknowledged making the unwise decision to down a half bottle of Grey Goose vodka probably helped. He entered a plea and was placed on probation for two years. If he kept his nose clean, the charges would be struck from his record. He did just that and, I’m happy to say, he has been walking the straight and narrow ever since that night.

Two things stick out for me from the incident.

One was my wife saying after Tyler’s sentencing hearing that she saw the assistant prosecutor respond with shock when he heard the terms of the plea agreement. He was visibly angry, she said. After the hearing Lirot said, “That prosecutor wanted your son to do serious time. He is a very lucky young man.” Sure, luck helped, but having the best possible attorney at that time was the real secret.

The other thing I remember was when Tyler finished his probation—no longer having to go in for monthly drug testing, or do community service, or check in with his probation officer—he framed the probation release paperwork and hung it on the wall like a college diploma. It was the happiest day of his life. He said, “Once you enter the criminal justice system, you are stuck in a machine that just grinds you down and chews you up, no matter who you are.” There are many adult club owners, managers and entertainers who have been unfairly sucked into that machine who would agree with Tyler.

Most ED readers familiar with Lirot’s First Amendment work in Florida might be surprised to hear that he also handles criminal cases. In fact, his legal practice covers many other areas of law in many other states.

“They were very upset that I would have the audacity to show those anatomical areas. So they kicked me out. It was my first taste of censorship.”

Lirot has handled cases that have generated over 200 published opinions. He has practiced in state and/or federal courts in over 20 states, including Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, South Carolina, Wisconsin, Delaware, New York, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Texas and Ohio. He is a past President of the First Amendment Lawyer’s Association (FALA), and a member of the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. He was selected to Super Lawyers for 2020-2023, a peer designation awarded only to a select number of accomplished attorneys in each state.

Lirot was invited to be part of ED’s Founders Interview Series because the series focuses on people, be they club operators or industry professionals, whose contribution to the growth and success of the industry has been substantial and long-running. Lirot is among a handful of First Amendment attorneys who have helped shepherd club owners through the always-turbulent waters of opening, operating and, most importantly, keeping open their adult nightclubs. He was on the legal panel at the very first Gentlemen’s Club EXPO 30 years ago and is one of the most well-known and recognized attorneys in our industry.

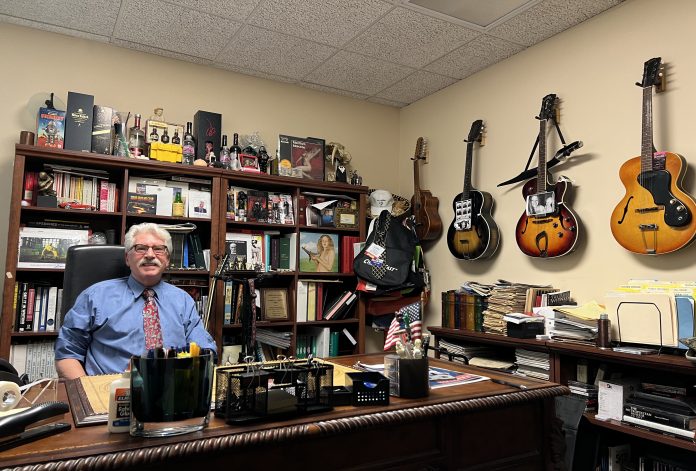

The word that best describes Luke Lirot is dapper.

He is dapper in both his appearance and his demeanor. You almost expect him to be British, maybe Hugh Grant from the movie Notting Hill.

But he’s American, so think Richard Gere instead from Pretty Woman. He is always dressed immaculately. He is friendly, polite and attentive. He never fails to ask you how you are doing, and always ends a conversation with a positive comment. He looks the same today as he did at that first EXPO three decades ago. His hair may be white now and no longer dark, but, to the consternation of many of us, it’s still a full head of thick, wavy hair. And of course there’s that signature mustache, one that even Magnum PI would be jealous of.

ED Marketing Director Kris Kay summed it up best when he said, “No matter who else is there, Luke Lirot will always be the coolest cat in the room.”

* * *

WAITT: How old are you know and where were you born?

LIROT: I’m 66 and I was born in New York City.

WAITT: Any brothers or sisters?

LIROT: I have two sisters. One is a retired lawyer and one is a production assistant in New York and a standup comedian.

WAITT: How did you end up in Clearwater, Florida?

LIROT: My family had dress shops. They had one in Stamford, CT, and one down here at the Belleview-Biltmore Hotel in Bellaire, FL. They used to spend half the year up there and half the year down here. When I turned four, we moved here permanently.

WAITT: Dress shops and New York? Shouldn’t you be Jewish?

LIROT: No, we’re Irish Catholic, with lots of great stories about heavy drinking.

WAITT: So your father was in the dress shop business?

LIROT: Actually, my mother was. My father was an engineer. My parents were divorced when I was very young, so my Mom was a single parent and worked the dress shops. She had a second job at night as well as the wire editor at the Clearwater Sun newspaper. So she held down two jobs. I used to be a copy boy there.

I went to Saint Cecilia’s in the first grade and I got kicked out for changing my grades with one of those large pencils with the big clunky eraser at the end. So my Mom drove me all the way to the Boys Academy, another Catholic school over in Tampa. But in the third grade I got expelled because I made a collage for a school project. (He made the collage by cutting out photos of half-naked models from his mother’s fashion magazines Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.) There were bras and legs coming out of the collage everywhere. The nuns back then were still wearing the full black habit and they were very upset that I would have the audacity to put such artwork together showing those anatomical areas.

So they kicked me out. It was my first run-in with censorship.

Lirot eventually made it to Jesuit High School, an all-boy high school run by Jesuit priests, where he managed to stay out of trouble, except for when he joined protests against the Vietnam War.

WAITT: Did you play sports? What were your interests then?

LIROT: I played football and tennis. And I was slowly learning to play guitar. I got a guitar for $20 at a pawn shop and an amp for $5. I had that guitar for the longest time. I probably have 50 guitars now, and I’m still struggling to be more competent musically. But I entertain myself quite well. That’s the purpose that it serves.

WAITT: So then you went to Florida State University in Tallahassee?

LIROT: Well, I went to the University of Florida in Gainesville first. I started there in 1974 and the drinking age in Florida was still 18 at the time. I became well-adapted to the two-for-ones and the nickel beer nights throughout Gainesville. On a very small budget, I managed to keep myself well-lubricated for two years. I was interested in criminology and the counselor told me I should go to Florida State which had a much better criminology program. I transferred there in ’76 and started the major in criminology.

WAITT: When you were majoring in criminology, was it with the the goal of being an attorney or doing something in law enforcement?

LIROT: I’d say 50 percent of it was looking at law enforcement, the nuts and bolts of the administration of police work. I took a couple of courses where we counseled kids who had witnessed violent crime. I also minored in photography and ran the photo lab at Florida State for a while. That’s when I had a another bout with censorship, when I entered a photo contest.

I had a box of old negatives from the 1890s that my great-uncle had kept. In it there were a lot of interesting poses of people trying to shield themselves from the sun. So I got some Penthouse magazines and I cut out the naked women and did a collage where it looked like these people from the 1890s were shielding themselves or trying to hide from the nude women. And I entered the collage into the contest and they said, “Oh no, you can’t put that up.”

And I said, “Why not? It’s really good and I worked hard to put this together.”

It was a big debate and eventually they let me put it up. But I guess it was a little too controversial. I didn’t win any prizes.

I really thought I would end up as a photographer at that point in time because I did lots of photographs. Around that time was when Ted Bundy did his damage at Florida State University and I was writing for the school paper. So, all of a sudden, instead of writing that two bikes were stolen from McPherson Dorm, now I’m going to these press conferences where they’re talking about Bundy. It was fascinating.

WAITT: You went to Florida State to get your bachelors degree, but then to the University of San Francisco School of Law to get your law degree. Why did you pick a college on the complete opposite side of the country?

LIROT: When my parents got divorced, I always stayed in touch with my Dad. He was in the construction business and he would find me jobs in the summer so I could make some money and see different places. He had moved to San Francisco, so when I graduated from high school I went out there and started working construction during the summers. I went out with another guy who had gone to Jesuit and we lived in downtown San Francisco. We had the time of our lives. We just had an absolute blast and met guys in the music industry who got us into all the concerts out there, like Journey and Eddie Money and Santana.

Lirot had decided to go to law school in San Francisco, but one more adventure awaited. His father helped get him a deckhand slot on a 120-foot Baltic Trader sailboat. On Halloween Day in 1979, the boat sailed under the Golden gate Bridge and turned left.

“We hit every port in Mexico worth going to. I made the princely sum of $25 a week, but room, board, everything else was covered. I didn’t have to buy a single grocery or a single beer. We went through the Panama Canal, and when we got to the Caribbean, they decided they wanted to stay there for a while. So for the next year and a half we went from island to island. We eventually went up to New York, and then they wanted to go around the world. My Dad said ‘You know, I didn’t expect you to do this forever. I thought you were gonna head to law school.’”

And I said, “You’re right.”

Lirot returned and enrolled at the University of San Francisco School of Law. “San Francisco was beautiful then. It wasn’t overwhelmed with homeless people like it is now. It was an absolutely wonderful place to be. That whole summer of love vibe was still floating in the air.”

“I’m thinking, would I rather represent exotic dancers or go to bankruptcy court and fight over math homework? It was a no-brainer for me.”

WAITT: You do realize that with a name like Luke Lirot your options for employment were limited; it was were either become a porn star or become an attorney in the adult entertainment field?

WAITT: You do realize that with a name like Luke Lirot your options for employment were limited; it was were either become a porn star or become an attorney in the adult entertainment field?

LIROT (smiling): The name Luke was the product of being the son of two Catholic parents. Lirot was my father’s name. Actually my father’s name was Brown but when his father passed away, his mom got remarried to Albert Lirot. And there you have it.

WAITT: The legal and medical fields offer many different specialties. People in med school become podiatrists or urologists or cardiologists. People in law school specialize in personal injury law or medical malpractice law or tax law. Why did you choose Constitutional Law and First Amendment Law?

LIROT: First, I had had all those bouts with censorship, going back to the third grade and getting kicked out of the Boys Academy where they literally tore up my collage, which was the best one of the bunch. That just freaked me out. And then I had the issue at Florida State with my contest entry. I was offended that I couldn’t show my art without a fight. And I was also lucky enough at the University of San Francisco to have a guy named John Denver, of all names, who was a really inspirational constitutional lawyer.

When I was going to the University of San Francisco I went to Ireland as part of a scholarship program to study human rights and what was going on in Northern Ireland with the IRA prisoners. Other than getting beat up by Clearwater cops after a high school football game for being too mouthy, I really had not had any contact with any police authority. But in Northern Ireland I was troubled by the way I was treated when we went to see some folks, and they were not interested in us doing anything to benefit IRA prisoners. That left a bad taste in my mouth.

Instinctively, First Amendment and Constitutional Law seemed a lot more fun to me than personal injury law. I did know that it was a much tougher way to make a living. You certainly don’t make the income that people who do other kinds of law make, like medical malpractice and personal injury. But you end up encountering a lot of people who need help that don’t have a dime.

WAITT: So you were making an intentional choice to do legal work that satisfied you personally and not necessarily your wallet?

LIROT: Yes.

Lirot graduated in 1986, and returned to Clearwater when he learned his mother had been diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He moved in to take care of her, but she soon passed away. “I’m depressed. And I’m thinking I gotta wrap things up and get back to California. But I was broke. I had passed the Florida bar in October of 1987 and I couldn’t find a job to save my life. I’m working at Kelly as a temp guy. I silk-screened a million Spuds MacKenzie lighters for Bud Light. To this day, if I see Spuds MacKenzie, I Pavlovian smell butane.”

Lirot landed a job with Tom Little, a bankruptcy and real estate attorney in Clearwater. The work was dry to say the least, but one day Little got a call from Joe Redner (of Mons Venus fame) who had opened a stripclub with full nudity in Pinellas County. His dancers kept getting arrested on lewdness charges and Redner needed help with the arraignments. Little, knowing Lirot had handled arraignments as a law intern while in San Francisco, asked Lirot if he was interested in helping Redner out. “I’m thinking, would I rather represent exotic dancers or go to bankruptcy court and fight over math homework?” recalls Lirot. “It was a no-brainer for me.”

Lirot hopped on board with Redner: “The club was called Rapture, and the sheriff and a lot of the religious zealots who were more outspoken and militant and numerous in those days, were upset that someone would call a stripclub a ‘rapture’ because of all of the religious connotations. So they would go out and arrest everyone.”

LIROT: I started to work for (Redner) and he was happy with the work I put in. I had some success in filing motions and challenging the statutes. He had other attorneys on other cases but at a certain point I thought I could do a better job than the team of guys he had. And he was spending a lot of money. I talked him into hiring me for a thousand bucks a week. I said I’ll do everything. So I was in-house for Redner. It was in a little one-bedroom house a block from Mons Venus that we called “The Bunker.”

A few days after that, I’m driving him to the airport in his beautiful white Cadillac, and we get pulled over. They tell Redner to lay in the grass right there at an overpass. And I said to the officers, “Well, I’m Mr. Redner’s lawyer.” And they said, “Fuck you, you’re laying in the grass, too.” So I’m laying there with bugs crawling up my nose and I’m thinking what have I gotten myself into?

WAITT: You convinced Redner to bring you in house. His primary motivation was probably saving money by paying just one attorney. But you two ended up being like Martin and Lewis, a winning duo. Why do you think that partnership worked for so long?

LIROT: For so many different reasons. First of all, I really respected Mr. Redner. This goes back to my protest days and standing up to the Vietnam War and all of that. He was arrested over 150 times. I thought he was a really staunch guy, and he did what he did for all the right reasons.

Now, he could be abrasive and he could be stubborn, and I figured that it was my privilege to help him work his way through some of those issues. When he did his show on public access TV, I joined him with that, which was an absolute blast. Philosophically, we have a ton in common even though we have different upbringings. We just became the dearest of friends.

WAITT: Do you think, for his part, Redner recognized that he could occasionally be too hard-nosed and he could benefit by teaming up with somebody who could smooth over situations?

LIROT: Yes. I think he recognized that I could help him diplomatically in any number of situations.

In 1990 Lirot opened his own law firm handling First Amendment, Constitutional Law and criminal cases. His offices are in Clearwater, which is on the St. Petersburg side of Tampa-St. Pete.

WAITT: At what point in this whole process did you get married?

LIROT: My first marriage was to Amanda Oliver, who was a dancer who had been arrested in Citrus County during a case I worked for Redner. I respected the fact that she went back three times and got arrested, and spent a lot of time in jail, for doing what she believed in. Our marriage only lasted about 11 months. I will concede it was the pressures of my profession and not hers that caused the most emotional strife for us. It was just one of those things that didn’t work out for different reasons.

WAITT: When did you get married again?

LIROT: In 1995 to my second wife, Traci. I just found her to be wonderful. She was a receptionist at a legal office, and I met her through representing her husband, who had been charged with attempted murder for running her and her infant daughter, who’s now my stepdaughter, off the road. We got married and my daughter, Lauren, was born. So now I’ve got two daughters. My stepdaughter, Alexis, has four children, my grandchildren, who are the loves of my life.

Traci and I, we’ve made it through thick and thin. It took her a long time to get used to the 4 am calls from nightclubs, because gentlemen’s clubs need my help during their business hours, not mine.

WAITT: As you became more well known in Tampa Bay as a champion of adult entertainment causes, what impact did that have on your wife and your daughters?

LIROT: Their friends weren’t allowed to spend the night at my house. People would look at me with disdain. I’d go to neighborhood or school functions and I would be completely ostracized. But the beauty of that is, fast forward 10 or 15 years, and those same people call me to represent their daughters when they become involved in criminal activity of one kind or another.

But it was tough. People would say, “Well, what would you do if your daughter was a dancer?” And I would answer, “I would wish her the best if that’s what she wanted to do.” I wouldn’t push her into it, but I wouldn’t push her away from it either. These are choices that they make.

Their mother probably would try to influence them one way or the other. But as far as I’m concerned, whatever aspersions you’re trying to cast on that as a career, I’m not buying into it. I would be a hypocrite to say that their freedom is any different from the freedom of the other people that I represent.

WAITT: If you were getting married today, don’t you think it would be easier on your wife and children? It seems people are a bit more tolerant now about stripclubs and entertainers.

LIROT: Yes, because back then it was miserable. Back then, if you went to a city council hearing there’d be 400 people there against you. The American Family Association wanted to have your head on a stick. It was very, very militant. I used to have a shoebox full of all the letters I got with death threats. I remember I went to represent Thee Dollhouse up in Myrtle Beach and some guy came up and had to be restrained by his friends from attacking me. He spit on me. Just because I was speaking in favor of Thee Dollhouse in opposition to a zoning ordinance.

“There’s not a single challenge faced by any business that isn’t also faced by gentlemen’s club owners. But for them it’s magnified a hundred times.”

WAITT: All of that hate because of bare breasts.

WAITT: All of that hate because of bare breasts.

LIROT: It was crazy.

WAITT: I was once asked by a Wall Street Journal reporter to describe what the typical adult nightclub owner is like, and I said: “Remember when you were sitting in class in high school bored out of your mind? And you looked out the window to the school parking lot and saw students skipping class. They were sitting on the hoods of their Camaros and Mustangs smoking Marlboro reds. Well, those are the guys who end up owning stripclubs.” Do you agree?

LIROT: I do. You gotta give them credit. It’s a lot harder than any other kind of business because you’re going to get, not only cultural and societal heat, but you’re also going to be fodder for any kind of political issues. There’s not a single challenge faced by any business that isn’t also faced by gentlemen’s club owners, but for them it’s magnified a hundred times. There are threats and challenges for them at every turn.

WAITT: Do you think being rebels who don’t like being told what they can and can’t do allows them to persevere as stripclub owners?

LIROT: Yes. It’s that rebelliousness, and their ability to stick to it, even in the face of challenge.

WAITT: That said, are club owners often their own worst enemies?

LIROT: They can be. Sometimes stubbornness replaces diplomacy. They’ve been abused and treated unjustly so often that sometimes it can lead to a callous approach. You have to work with the system in order to be successful, but at the same time, you don’t want to be pushed around. You don’t want to be weak, and you have to be able to stand up for what you believe in.

WAITT: I have found that club owners, be they small blue-collar clubs or large white-collar clubs, consider themselves kings of their castle. Some of them have big egos, and they want things done their way, whether it’s right or wrong. Do you find that to be a challenge, as opposed to working with clients from other walks of life?

LIROT: Absolutely. No question about it. Club owners have to be sold on anything other than full speed ahead. They usually want a take-no-hostages approach. I love that. It makes it interesting. But once you can explain things in a way that gives them the ability to make a fully-informed decision and you tell them why, they will listen.

I tell them that banging your head against the wall is not the right thing to do. That we really should approach it from this other perspective. And more often than not, it works. And when you’ve made it work for one guy in one jurisdiction and word gets out about that success, the other guys who might have been a little bit more stubborn will now listen to you. They are much more accepting of different strategies if they’re shown prior success.

WAITT: When you are asked to represent a club because of a supposed violation, how often is it because of something the club owner did or mandated versus something a manager or a staffer did?

LIROT: Operationally, it’s usually the managers. For instance, I’m dealing with some personal injury suits where the owner is on the hook because the management wasn’t diligent enough in getting security to do what they were supposed to do. The story I hear is that they were watching the fight, rooting for one of the participants. Operationally, the owners seem to be very disciplined. They have really good policies and procedures, but, like every other profession, it’s hard to find good help.

WAITT: If you could gather every adult nightclub operator in the country into one giant room and give them three pieces of advice, what would that advice be?

LIROT: The first is, maintain a high level of diplomacy. Even though it may seem impossible. No matter how hard it is, remain diplomatic.

WAITT: With whom?

LIROT: With everyone. Certainly starting with the people in power.

WAITT: And the other tips?

LIROT: Second, don’t let anybody push you around. Which may seem counter to the first point about being diplomatic. You have to find a way to reconcile number one and number two.

And the third piece of advice is, trust your instincts. If somebody is giving you a good story, but something feels a little bit off, whether it be a performer or a manager or a service provider, trust your instincts and dig a little deeper. See if there’s any merit to the suspicion that you have.

WAITT: I’m not sure if these two riddles will ever be solved: 1) What came first, the chicken or the egg? or 2) Are stripclub entertainers employees or independent contractors? Your thoughts?

LIROT: People know that every decision in the last 20 years has found exotic dancers must be classified as employees. Not because of some flaw in our industry, but because of the inherent flaws in the Fair Labor Standards Act—this one-size-fits-all federal regulation which has absolutely no application to the gentlemen’s club business model. There is not a dancer in this country that if she puts her cigarette down and goes out into the club can’t make many multiples of minimum wage. And she gets the benefit of every dime of investment and expense that an owner has put into the physical structure, the security, the liquor license, the liquor inventory, and the other people that work there. And she gets that for nickels a day, and she’s able to make as much money as she wants based on her own initiative. That’s an incredible deal. Those are the worst cases that I can handle because they’re based on a legal theory that has no application to this industry and it’s a license to steal. It really is.

It’s so frustrating that these performers don’t care. What really bothered me early on was that when dancers file Fair Labor Standards Act cases, it’s an admission that the negative characteristics the moral majority holds against dancers—that they are dishonest and deceitful—validates those negative views. I’ve represented well over 2,500 dancers (arrested at clubs). They don’t pay their legal fees. The club owners do. The club owners have taken care of these people like members of their own family.

WAITT: Who are some clubs owners whose business acumen and creative thinking have impressed you over the years and why?

LIROT: I’d start with Mr. Redner. His steadfast approach to everything he does can be viewed as being stubborn, but I view it as being highly disciplined. So he’d be at the top of my list because he’s my first guy.

Michael Peter, just because of his creativity, he’s high on the list. Slim Baucom is also high on the list because he’s just the quiet genius. You know, he doesn’t have a lot to say, but when he does say something, it’s usually profound. I’m a big fan of Jim St. John and Harry Mohney.

The best part of doing this is that there’s this camaraderie, the shared baptism under fire that you get when you work with anybody associated with this business.

From a cultural standpoint, they’re open-minded. They understand that human sexuality is a huge part of every aspect of human life. Back in the day, it was wonderful to represent naked women. It still is. It’s just something that’s so fun and the fact that it flies in the face of a lot of cultural morays. I’m rebellious at heart, so it satisfies that innate urge that I have.

Dealing with the folks that are in this industry, I don’t dislike any of them. Some of them are brighter than others. Some of them are more stubborn than others. But going through what they’ve gone through, I think the average level of acumen of the people that run businesses in this industry is vastly greater than the average level of acumen of people that run any other kind of business. And I’m talking about restaurants, nightclubs, what have you.

When you’ve had to develop skills, under the crucible of fire, to operate these clubs successfully, then you’ve developed something unique and special. It’s hard to put a finger on it, but it is palpable when you’re in a group of people that are associated with this industry.

WAITT: You have dealt with, and represented, entertainers for more than three decades. How are the entertainers of today different than the ones from 20 years ago?

LIROT: I don’t think they have any knowledge of the sacrifices and the battles that we have waged over the years just to keep these clubs open, from being zoned or regulated to the point of complete failure. They don’t know about the cultural crusade we went through just to be able to operate a club and give them the ability to make a comfortable living.

WAITT: Club owners aren’t shy about saying that attorneys are a necessary evil. Some of them think attorneys over-complicate issues to keep the billing meter going. Do you think the First Amendment attorneys in this industry get the respect they deserve?

LIROT: I think they do. Certainly from the people who are familiar with this industry. I don’t think they view us as avaricious or as trying to line our own pockets by complicating cases beyond what they need be. Make no mistake about it, with each passing day, there are new decisions that make our ability to represent our clients that much harder. We have to continually try to be more creative and more hardworking.

We’re fighting cities and counties, and everybody on that side has unlimited resources. They’ve got all the time and money in the world to fight, especially if they are dealing with just one club. The people who practice this kind of law, I don’t think they’re in it for the money or they would be doing something else. It’s obvious that virtually every other area of the law is much easier to deal with and is much more highly compensated.

This is a lot of hard work and it’ll break your heart day after day, and you have to be really tough. I was here last night until 2 am and I’m 66 years old. I didn’t think I’d still be doing this, but here I am.

“If I can help owners solve a problem before I need to participate … then I’ve paid it forward to the industry that’s fed me for the last 35 years.”

WAITT: You and many of your fellow First Amendment attorneys have been generous with your time with ED Publications, writing columns for the magazine, sitting on legal panels at the EXPO, etc. The irony is you all have done such a good job educating our readers and show attendees that you may have occasionally cost yourselves paying clients.

WAITT: You and many of your fellow First Amendment attorneys have been generous with your time with ED Publications, writing columns for the magazine, sitting on legal panels at the EXPO, etc. The irony is you all have done such a good job educating our readers and show attendees that you may have occasionally cost yourselves paying clients.

LIROT: There could be club operators who walked out of a panel session, implemented something they heard at the session, and thus did not need an attorney. When I go to EXPO and I’m on these panels, nothing makes me happier than making myself obsolete. If I can help owners solve a problem before I need to participate in helping them solve the problem, then I’ve paid it forward to the industry that’s fed me for the last 35 years.

Dave Manack, now ED’s Publisher, has been at ED for more than 25 years. And to this day, he still carries in his wallet a small, folded piece of paper. On it is Luke Lirot’s name and phone number. “I’ve always carried it,” says Manack, “just in case I need him in a pinch.”

A few years after starting the EXPO, I found myself in a pinch when we held the conference at the El Dorado Resort & Casino in Reno. We did a dancer contest the first night, with clubs entering their best dancers in the competition. The next day a manager approached me and said his club owner was upset his dancer had not won the contest. He said the owner, who was a high roller staying in the biggest suite at the El Dorado, was going to call casino management and tell them to cancel the EXPO.

Holy shit! I found Luke Lirot, who was a scheduled panelist, and explained the situation.

“Let’s go see the man,” said Lirot.

When we got to the owner’s suite it was packed with a dozen people with angry faces. Lirot nodded at me to sit on a couch off to the side, then he took a chair from the dining area table and very slowly dragged it smack dab into the middle of the suite and sat in it facing the owner. He looked around the suite and saw a fully stocked bar.

“Before we get started,” said Lirot, “would it be possible to get a cocktail?”

Which suprised the hell out of everybody.

The owner had one of his managers make the cocktail. Then, with cocktail in hand, Lirot looked the club owner straight in the eye and said, “Okay, now let’s see how we can get all this resolved.”

Thirty minutes later everybody in the room was shaking hands.

The dancer who had lost had stopped crying.

The dozen people with angry faces were smiling.

The club owner was smiling.

Lirot was smiling.

Me, I was breathing again.

WAITT: When you speak, be it in person or on a panel at EXPO or at an ACE National Board meeting, club operators can actually follow and understand what you are saying. Unfortunately, that’s not true with many attorneys who get so deep into case law and legal terms that the eyes of who they are addressing start to gloss over. Do you make a conscious effort to speak in a way that non-attorneys can easily follow?

LIROT: There are a couple of elements to that. A lot of times, I see attorneys trying to explain things in lofty levels of legalese because I think it makes them feel like they’re smarter. If they understand it and the person they’re talking to doesn’t, then there’s that feeling that I must be smarter than you. But what does that accomplish? Nothing. So that’s just selfish. If you take the time to communicate logically, clearly, and effectively with other people, then your goal is met. I feel better when somebody’s lights go on and they understand what I’m telling them. It gives me a level of satisfaction.

“A lot of times I see attorneys try to explain things in lofty levels of legalese because it makes them feel like they’re smarter. But what does that accomplish?”

WAITT: You recently represented a small town mayor, Scott Tremblay, who got into trouble for driving a utility vehicle on a particular road. You issued a statement saying it was “unfortunate Mr. Tremblay’s efforts to inspire a positive change from the colorful and rambunctious history that made Port Richey more of a shudder than a shining star on Florida’s Gulf Coast have been reduced to guff over golf carts, but so be it.” That text sounds more like Shakespeare than a legal argument. You certainly have a fondness for a well-turned phrase.

WAITT: You recently represented a small town mayor, Scott Tremblay, who got into trouble for driving a utility vehicle on a particular road. You issued a statement saying it was “unfortunate Mr. Tremblay’s efforts to inspire a positive change from the colorful and rambunctious history that made Port Richey more of a shudder than a shining star on Florida’s Gulf Coast have been reduced to guff over golf carts, but so be it.” That text sounds more like Shakespeare than a legal argument. You certainly have a fondness for a well-turned phrase.

LIROT: I’m very proud of that. I try to put a smile on everybody’s face that I communicate with, because it opens the doors and helps you reach a better resolution.

I remember early on going to a local ordinance court where they brought dancers arrested for exposing their cleavage or buttocks in a business licensed to sell alcohol. The guy ahead of us was charged with owning a house that was a neighborhood eyesore because the paint was peeling off the house. So when I got up there next, in front of this very old judge, I said, “Well, your honor, the allegations against my client would also peel the paint off the wall. Let’s get into this case!” I like to add a little flourish in a way that’s humorous and entertaining, but also gets the message across.

WAITT: In that same statement you wrote, “His opponents have made accusations of improper conduct related to this humble form of perambulation.” Did you really use the word “perambulation?”

LIROT: I’ve been known to use words like that. I’ve always had a good time with vocabulary.

WAITT: I think it’s interesting that in the 30 years I’ve been in this industry, I know of only one attorney who ended up owning a stripclub. Why do you think more attorneys have not gotten into the ownership side of this business?

LIROT: A lack of vision? Not having the wherewithal to make that kind of an investment because we’re so challenged in our income from this difficult area of law?

I wish I could afford to. But you know, I’m on the Board of RCI (Rick’s Cabaret) which is an incredible privilege. Everybody I work with there is absolutely wonderful. They’re brilliant. We get to step outside of the social morays and we are publicly trading on the stock market, which add adds validation to this entire industry. Doing that work on the Board satisfies my entrepreneurial bent about club ownership.

WAITT: Do you think another reason is that attorneys see first-hand how tough it is to own a stripclub?

LIROT: Subconsciously that could be one of the reasons. Because not only do you deal with every aspect of governmental permitting and entitlement challenges, but there are personal injury suits, unauthorized use of images suits, Fair Labor Standards Act suits, and on and on. And the fact that you are dealing with exotic dancers of a youthful age who can be a real headache.

WAITT: What is the highest court you have taken your cases to?

LIROT: I’ve filed several cases in the United States Supreme Court, but I’ve never had one accepted for cert (case review). But I have argued in several Circuit Courts of Appeal and 35 different state courts of every level.

“I try to put a smile on everybody’s face that I communicate with, because it opens the doors and helps you reach a better resolution.”

WAITT: From my days as a newspaper reporter, I found that the most powerful person in a city was not the mayor or the chief of police. It was the federal judge in that district. Federal judges can be quite intimidating.

WAITT: From my days as a newspaper reporter, I found that the most powerful person in a city was not the mayor or the chief of police. It was the federal judge in that district. Federal judges can be quite intimidating.

LIROT: They are, but you have to remember that you’re there to help them do the right thing. So you need to be clear and prepared, and be able to explain what the right thing is with a little bit of case law to back you up. They’re usually very friendly. I’ve had a couple of things happen to me that probably were not appropriate, but I handle it because it comes with the territory.

WAITT: What would you consider your three biggest legal victories to be in the adult entertainment arena?

LIROT: One of my favorites is Redner versus Dean, recognizing that nude dancing is protected by the First Amendment. There have been some things to chip away at that, but that was a major victory. Another one was the Voyeur Dorm case where they tried to close down the Voyeur Dorm as an adult business. It was one of the very first cases, certainly in the 11th Circuit, to recognize that the internet is different than a brick and mortar business. Back then that was not as established as it is now, and it was one of the initial decisions to get that accomplished.

And the Citrus County case involving Redner was one of the big ones, particularly with Redner getting money back. There’s nothing more fun than getting a big check from a municipality. When a county has basically done everything they can to stomp your client out of existence and you’ve convinced the court or a jury that what they did was wrong, they have to write your client a check.

I remember one case where Redner got closed down in Hillsborough County and we filed a lawsuit against the county. We had a trial and I’m arguing. The jury’s looking at me, but I’m not getting any feedback, no head nods or warm eye contact. So I have no idea how I’m doing. And we were looking for money. We take a break for lunch and all of a sudden my phone rings and I’m like, oh no, the jury can’t be back this quick. We go back and the judge says the jury would like to know if they can have a calculator (to compute how much to pay out). Oh, wow. I ran over to the Walgreens, which was a block away from the Federal courthouse in Tampa. I got ‘em the biggest calculator that I could buy.

The best part of decisions like that is people using those cases in other areas to support broader First Amendment issues. That brings me great pride.

WAITT: Why do you think sexually-oriented businesses are targeted by politicians and law enforcement more than other businesses? What is their real motivation for going after SOBs? Isn’t it really just for exposure, to enhance their careers?

LIROT: Everybody has the fire down below and a lot of people will criticize in public what they embrace in private. We’ve seen that time after time. But there’s also this erroneous belief in America that if you take a very conservative approach to human sexuality in our culture, then you are deemed to be a more moral, better person. There is this misguided belief that being restrictive towards human sexuality is a good thing, right? When in fact, just the opposite is true.

WAITT: Who’s more powerful, the media or the government?

LIROT: The media can set the pace. If the media can take a more realistic and, shall I say, less misinformed and misguided approach to these issues, then the hypocrisy that drives these issues becomes less appealing to our elected officials. If the media is fair and honest …

WAITT: Did you just use the words media and fair in the same sentence?

LIROT: I try. But it really comes down to, what is it that politicians think will appeal to the largest number of people so they can get re-elected? It’s just basic math.

“There’s this erroneous belief in America that if you take a conservative approach to human sexuality, then you are deemed a more moral, better person.”

WAITT: Was Tampa the birthplace of the infamous six-foot rule, or was that happening around the country?

WAITT: Was Tampa the birthplace of the infamous six-foot rule, or was that happening around the country?

LIROT: No, actually there’s a case called Kev, Inc. versus Kitsap County out of Washington, where it was a 10-foot rule. That’s the first case where they discussed some distance restriction, but it wasn’t until Tampa and the six-foot rule that it took on the dimensions that it has. It’s still on the books and has been deemed to be good law. They just know that it can’t be enforced.

WAITT: Is Tampa the birthplace of any other well-known restrictions that our industry has faced?

LIROT: Not really, but Tampa is probably the genesis of the lap dance, so to speak. Now I know a lot of people put it at different locations at different times, but I think that it really developed here, sort of in response to a lot of the restrictions on alcohol and trying to come up with ways to be more competitive. With Michael Peter and Redner and the friction dances, I think it began here.

WAITT: It seems to me that among the states, Florida is the leader in the stripclub business. The three biggest booking agencies—Continental, A-List/Lee Network and Pure Talent—were all based here. Michael J. Peter’s Thee Dollhouse/Solid Gold/Pure Platinum chain was based here. The biggest stripclub in the country, Tootsies’ Cabaret, and the most high-tech cutting edge club in the country, E11EVEN, are both in Florida. Mons Venus and 2001 Odyssey are famous nude clubs. There are 170 adult nightclubs in Florida, more than any other state. Some of the industry’s top attorneys, like yourself, Danny Aaronson, Jamie Benjamin are here.

LIROT: Well, obviously let’s just get the climate out of the way. We don’t have to go to the clubs on our snowmobiles like my clients in Wisconsin have to do for half the year. A lot of it just comes from the fact that Florida was predicated on tourism. And being able to attract people from elsewhere by presenting different types of entertainment that want to bring you here. In Florida, one of its core goals is to be hospitable. That’s a huge part of it.

WAITT: Why are adult nightclubs classified as SOBs in the first place? There is no sex occurring at stripclubs, or at least there isn’t supposed to be any. So why does the word “sex” even enter the picture?

LIROT: They thought it was a nice way to use the SOB acronym—Son of a Bitch—to place adult clubs in a bad light. Some of the major opponents, like Scott Berghold, people who go all over the country being handsomely paid for opposing clubs like the plague, it offends their religious beliefs. They are not comfortable with women who get naked and are compensated for that, even if it is in the context of expressing a message. It just shows that power can be abused. Call us whatever you want to call us, but give us the license. Let us open and operate and do the job.

“It just shows that power can be abused. Call us whatever you want to call us, but give us the license. Let us open and operate and do the job.”

WAITT: But why is the word “sex” even in the license name?

WAITT: But why is the word “sex” even in the license name?

LIROT: That’s where you get down to definitions because they can call it whatever they want, right? They define it by the exposure of anatomical areas that are involved in sexual activities and which involve some kind of gyration or movement of those anatomical areas. Even though it’s essentially the sizzle and not the steak. I don’t know if gentlemen’s clubs are sexually oriented businesses as much as they are Hospitality Oriented Businesses or Entertainment Oriented Businesses.

A few hours before our interview time of 10 am, Lirot had called my cell. “Can we push the time back a little?

I’m still working on a pleading. Can we do 10:30?”

“Of course,” I say.

“Okay, thank you, brother.”

Lirot says the word “brother” a lot.

Most people say “man,” as in, ”Okay, thank you man.”

Not Lirot. He’s a brother kind of guy. It’s one of his trademarks. When you realize that Lirot is a child of the ‘60s, who joined Vietnam War Protests in the ‘70s, who spent years in San Francisco with the hippies during the Summers of Love, who traveled around the world for over a year as a bare-foot deckmate on a 120-foot sailing boat, and who has been playing and collecting guitars for half a century, then it just stands to reason the man is going to refer to you as brother.

WAITT: You were a speaker at the very first Gentlemen’s Club Owners EXPO at the Stardust in 1993 and have attended almost every EXPO since, usually as a featured speaker. You have been an advisory attorney to ACE National for many years, and you were inducted into the ED Hall of Fame in 2010. Why is it important to support these conventions and organizations?

LIROT: It makes me feel that I’ve done something good for people that I care about, and it’s always good to help people. There are so many reasons this industry is special, from the business success that people can achieve to their ability to employ and help other people make a living. There’s certainly a huge, if not subconscious, part of this business that allows us to be rebellious, to not be labeled as just automations that have no heart, no soul, no sex appeal.

WAITT: You have had a few bouts with cancer. Where do you stand now health-wise?

LIROT (who saw his doctor the day before this interview): As of yesterday, total remission. I had prostate cancer back in 2020, and I had my prostate removed, which knocked the wind out of me for a couple months. I recovered completely from that. Then last year I was diagnosed with bladder cancer, so I went through three months of radiation treatment. You’re worn out from doing it, getting zapped with the radiation, but it all worked. I feel better now than I ever have, to be honest with you.

WAITT: In the old days you were a bit of a wild man when it came to enjoying life. Some of your escapades are part of the lore of this industry. Have you settled down?

LIROT: I think age is a big component of that. I stopped drinking because I wanted to be able to get the best results that I could out of my radiation treatments. Quite honestly, I’m a nice drunk nine out of 10 days, but that 10th day was the one that caused me the most trouble. Every problem I’ve ever had in my life, when I get down to the bottom line, I can trace it to alcohol.

Now I’m sure I will drink again, but right now I’m not. And I don’t know that I’ve calmed down. I mean, from a mental standpoint, my sense of humor and those things have remained intact. So I don’t think I’ve become dull. But I don’t make as many bad decisions.

WAITT: You are a busy man with a full calendar of depositions, hearings and court appearances. I know that personally. We live in the same city and it took me a week to track you down. Are you working too hard? Are you ready to slow down a little?

LIROT: I don’t know what I could do that would bring me this level of satisfaction, so I’m going to continue to do this. Until I can’t, or until I don’t feel I can perform to the level where I’m satisfied with my productivity.

“There’s certainly a huge part of this business that allows us to be rebellious, to not be labeled as just automations with no heart, no soul, no sex appeal.”

WAITT: When you do have some “me time,” how do you spend it?

WAITT: When you do have some “me time,” how do you spend it?

LIROT: I like to play the guitar and I like to spend time with my grandkids. I have twin autistic grandchildren. Those little guys up there in that picture (he points to his office wall), they’re both autistic. One of them is non-verbal. So that presents a whole new level of experience to me. But they know how to love me and I know how to love them. And I’ve discovered that beyond that, everything else is just details.

I have a three-year-old granddaughter who is a hoot. And I’ve got a 10-year-old grandson. He’s great. He fishes, he rides his bike. So I mean, it’s just a nice taste of the American dream there. So I spend time with them and with my wife.

WAITT: I’m starting this interview with the story about how you helped my son out of a real jam years ago. He’s happily married now; he just had his first child, my first grandchild, with another child on the way. I’m very cognizant of how all of that might not have happened had he had the misfortune of going to prison. He would have come out a different person. I’ve thanked you over the years, and I thank you again.

LIROT: It was my privilege, brother.

WAITT: I have three favorite sayings that I use all the time. The first is attributed to Albert Einstein who reportedly said, “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.”

The other two came from industry people. One came from Randy Beasley, who always says, “It is what it is.” I love that one.

The other I heard you say years ago at an ACE National Board meeting. I know you weren’t the first to say it, but I heard it from you first. What you said was, “No good deed goes unpunished.” Why that saying?

LIROT: It’s unavoidable that when you’re trying to help people, there’s going to be some adversity that attaches to that. Either when the burden of what you’ve embraced turns out to be a lot harder than you expected it to be, or when someone turns out to not be as grateful for what you’ve done for them as you hoped they would be. There’s a lot of that.

WAITT: Last question. If you had a crystal ball and could look into the future, what do you see in the coming decades for the adult nightclub industry?

LIROT: I think the clubs will continue to thrive. As long as they are run to the level of dedication and expertise that your (EDs) efforts have tried to enhance and my efforts have tried to protect, I see no reason why they can’t be much more successful or at least maintain the high levels of success they’ve already achieved. We’ve gotten past a lot of the, what I’ll call, misguided cultural challenges that were so rampant back in the day.

If we can iron out things like the Fair Labor Standards Act and get people to be a little bit more careful so we don’t have all these lawsuits, and there isn’t another cause that has plaintiff attorneys lining up to take a poke at us, I think we will be just fine.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE: The Founders Interview with the man who built one of the most creatively named and successful club chains in the history of this business—Spearmint Rhino’s John Gray.