The Founders Interview

A conversation with

Duncan & Scott Burch

Of Burch Management and Mavericks of the Dallas/Fort Worth Market

Interview and story by ED Founder Don Waitt

(NOTE: This story appears in the March 2024 issue of ED Magazine.)

T

he waiter brought me an iced tea. I had ordered a Diet Coke. I noticed, but didn’t say anything.

Duncan Burch, on the other hand, did.

We were at lunch at a Mexican restaurant in Dallas where I had flown to interview brothers Duncan and Scott Burch for the ED Founders Interview Series.

Duncan, who had been telling a story, stopped and said, “You ordered a Diet Coke, not an iced tea.”

“It’s no problem,” I said.

Duncan caught the eye of our waiter and motioned him over. Gesturing toward me, he said calmly, “He ordered a Diet Coke, not an iced tea.”

The waiter apologized and said he would get the proper drink right away.

“Thank you,” said Duncan.

Everything you need to know about Duncan Burch can be found in that exchange. Duncan is the founder of an empire of adult nightclubs in the Dallas and Fort Worth markets, owning at one time three of the most famous clubs in the history of our industry: Baby Dolls Saloon, the Million Dollar Saloon and Cabaret Royale. He recently sold his last five adult clubs to RCI International for $66.5 million dollars. He still owns two gigantic country and western showbars in Dallas and San Antonio and is building a third in Houston. And he owns lots and lots of real estate in the DFW area. His phone chimes constantly while we are at lunch, but he just looks at who is calling and doesn’t answer, as a courtesy to me, his guest.

In short, the man is incredibly wealthy, incredibly busy and incredibly talented. And amidst the clamor in a busy Mexican restaurant, here’s what Duncan does.

He remembers what I ordered.

He notices when I do not get what I ordered.

He fixes the problem.

And he does so in a very calm, very polite way.

That attention to detail, that ability to quickly rectify a problem, and, most importantly, that desire to make sure his guests—be it someone from ED Publications or the tens of thousands of customers who have frequented his clubs—have an enjoyable time is why Duncan Burch has been so successful.

We are having lunch at Pappasito’s Cantina located near Baby Dolls Saloon and one of Duncan’s country showbars, Cowboys Red River Dancehall and Saloon. The food is plentiful and delicious, two adjectives that could be applied to the many clubs under the Burch Management umbrella over the years.

I know that as a fact, personally.

ED Publications was started in Dallas/Fort Worth back in 1991 when I lived here. So I am familiar with the market, the clubs, and the role Duncan and Scott Burch played in making it one of the top stripclub destinations in the country. I spent many an hour, and many a dollar, in Burch clubs back in the day.

Even before moving to Fort Worth, as a college student in nearby Shreveport, Louisiana, myself and many other adventurous young men would make the three-hour drive due west on I-20 to Dallas to explore the deliciously tawdry stripclubs there.

My favorite was Lipstick Cabaret on Harry Hines—no cover, cheap longneck beers, hard rock music, and friendly dancers who had never heard of VIP or champagne rooms.

Burch Management was started by Duncan when he acquired his first club, called Deja Vu, back in 1986. His brother, Scott, came on board a few years later after Duncan springboarded from owning one adult nightclub to owning many.

Spend a few minutes with them and you know they are brothers by the easy rapport between them. But visually, they look worlds apart. Duncan, who I have to say looks less like a stripclub kingpin than any other stripclub mogul I have ever met, dresses casually, has a laid-back personality and has his trademark ponytail that goes all the way down his back. He looks like he would be more comfortable at a Grateful Dead concert than in a stripclub. On the flip side, Scott, with his close cropped, salt and pepper hair, appears preppy and looks like he should be drinking a martini, shaken not stirred, at the country club.

Scott had picked me up at DFW Airport and then we drove to Baby Dolls Saloon to meet with Duncan. From there we hit the lunch restaurant, and then the conference room at Cowboys Red River Dancehall Saloon to do the interview. Scott took different routes to avoid DFW traffic, as he and Duncan know the city like the back of their hands. As we drove, Scott pointed out landmarks. He pointed to a brand new hotel and casually said, “Duncan sold them the land for that property.”

“I wanted to be up and in the clubs until 6 am, and Scott wanted to be in the office at 6 am.

So it was a blessing for me.”

—Duncan

Scott and Duncan are both wearing plaid, long-sleeve shirts because it’s chilly in Dallas that day. There are no expensive watches or flashy jewelry, proving once again that you can’t judge a book by its cover.

Like with a few of the other founders I’ve already interviewed, this was a hard interview to get. Duncan does not like publicity and does not like being in the spotlight. He said ‘no’ several times before I reached out to Scott to plead ED’s case. About a month later I received a text from Scott: “He’ll do the interview.”

Two weeks later I’m with Duncan and Scott at Pappasito’s Cantina.

Drinking a Diet Coke. Like I ordered.

* * *

WAITT: The obvious first question is, who is the oldest? And where were you born?

SCOTT: We were both born in Dallas. Me in 1953, Duncan in 1957.

WAITT: Did you have other brothers or sisters?

DUNCAN: We had one brother. He was killed in an auto accident 15 years ago. And we have one sister. She’s the oldest.

WAITT: What did your father do for a living?

DUNCAN: He was a manufacturer’s rep for the plumbing industry.

WAITT: Were either of you interested in following in his footsteps?

SCOTT: We both were. I worked in it quite a bit.

WAITT: What about sports and hobbies growing up?

DUNCAN: Scott was a lot more into sports. I played zero sports. I wanted to be at my dad’s office and work, work, work. Whether it was mowing yards in the neighborhood or being in his office.

WAITT: Because you wanted to earn some pocket money?

DUNCAN: No, it was because I loved hanging out with my dad. My mother would pick me up from school and take me to his office after school when I was little. I just wanted to drive the forklift and clean up the warehouse. I liked to impress him. Maybe that’s it; I wanted to get some ‘attaboys’ from Dad, right?

WAITT: Is there something you learned from your father that you used in building your club business?

DUNCAN: Oh gosh, Don, I’m sure there’s a tremendous amount I learned. For me to sit here and try to cherry pick certain things …

SCOTT: It was his respect for life and the work. The work ethic.

DUNCAN: I think 100 percent of whatever I have came from him and my Mom.

SCOTT: Dad worked for somebody else and then opened his own business and we saw what it took and what he had to do. I don’t want to put words in Duncan’s mouth, but I think that’s what he got out of it, seeing what it took to grow and build a business.

WAITT: Did either of you go to college?

DUNCAN: I was going to go to Texas Tech and do what college guys do, maybe a little bit of school and a lot of goofing off. A customer of my dad’s in East Texas owed us a bunch of money and we went down to try to collect it, but the plastic pipe company had gone out of business. We wound up buying the company. I was 18 at the time, so I dropped out of Texas Tech and went and operated it.

WAITT: The longer a founder operates in this industry, the more urban myths spring up about them. Duncan, I heard the only reason you went into the adult nightclub business is that you owned a plumbing supply company, you loaned a friend some money, he couldn’t pay it back and instead he gave you the keys to a small stripclub he owned and you reluctantly took it over. True or false?

DUNCAN: I co-signed on a note at the bank to get the guy a loan. After a year he hadn’t made a single payment. It was supposed to be monthly installments. The bank called the note in and then called me to pay it. So ultimately we took the club and started operating it in 1984. The club was called Deja Vu.

WAITT: Was your first club, Deja Vu, operating before Harry Mohney’s Deja Vu club chain? Did either of you contact the other about name infringement?

DUNCAN: We bought it in 1986 and it had been Deja Vu for two or three years before that. I don’t know if Harry had the name at that time. We might have been operating before them. Nobody ever called. We did get a letter about eight years ago, but the club had been closed for years.

WAITT: Burch Management was founded in 1986. Was that company started as a company for the adult clubs?

DUNCAN: Yes, exclusively for the adult clubs.

WAITT: Were you both involved in Burch Management from the beginning or did you come in later, Scott?

SCOTT: I came in later.

WAITT: There are some father-and-son teams running clubs, but there aren’t that many clubs run by brothers. I can think of Dennis and Ken DeGori of Club E11EVEN in Miami, Jim and Artie Mitchell of the O’Farrell Theater in San Francisco, Larry and Jimmy Flynt of Hustler and the Zanzucchi brothers from Arizona. What are the pros and cons of being brothers, working together in the same business?

DUNCAN: There have really been no cons for us. One of the pros is the trust. And our personalities are pretty different and our lifestyles are different. I wanted to be up and in the clubs until 6 am, and Scott wanted to be in the office at 6 am. So it was a blessing for me. I knew he would be in there taking care of things during the day, and I wanted to be on the club floor where the cash registers were, trying to create atmosphere in the clubs.

SCOTT: There wasn’t ever a con to the arrangement. I worked 100 percent for him.

WAITT: What did you know about running an adult nightclub?

DUNCAN: Nothing. We grew up in a pretty strict Southern Baptist family. There wasn’t any drinking going on and we didn’t know a lot about dancing and nightclubs. The only thing we could do was the same stuff we saw my Dad do in his business. And that was take care of your customers, treat people right and treat your employees right. So that was our philosophy. And we went in and started doing that immediately. And the sales just skyrocketed.

WAITT: So it was on the job training?

DUNCAN: Absolutely.

WAITT: When Deja Vu first fell into your lap, it had to have been an inconvenience.

DUNCAN: It was, but it turned out to be a lucky, lucky break.

There was another adult club in that strip center where Deja Vu was called Baby Dolls Saloon, owned by Mike Murphy. As Deja Vu started doing better business, Duncan’s club began taking customers from Baby Dolls Saloon. An unhappy Murphy reached out to Duncan and said he was going to cause problems with his lease and get him booted out.

Duncan had a better idea.

“Why don’t you sell me Baby Dolls?” he said. Duncan had done so well with Deja Vu that he had socked away enough money to be able to make the offer. Murphy accepted and when Duncan applied his secret for success from Deja Vu to Baby Dolls, that club also took off. Murphy was not upset; in fact, he later partnered with Duncan on opening the country and western showbars.

Over the years, Duncan has had strategic partnerships with a number of key players in the Dallas, Fort Worth and Houston markets. One of his most successful was with Nick Mehmeti who started with PT’s in Dallas in 1983. They combined Burch Management and Mehmeti’s company, Main Stage Entertainment, and formed B&M Management. The new company was the focus of a cover story in the June 2000 issue of ED Magazine, and I interviewed both Duncan and Nick for the article.

WAITT: Two names that play a prominent role in the Burch story are Mike Murphy and Nick Mehmeti. So how did they factor into the clubs?

DUNCAN: Mike Murphy is my partner here at Red River currently, and he’s who I bought Baby Dolls Dallas, Baby Dolls Fort Worth and The Fare from.

WAITT: How old were you when you bought Baby Dolls??

DUNCAN: Twenty-five-ish.

“We were competing with ourselves. We had to put a little different taste and a little different hook into each club.”

—Duncan

WAITT: Where did you get money to buy that club?

WAITT: Where did you get money to buy that club?

DUNCAN: I had been at Deja Vu about a year. I had stacked up several hundred thousand in the bank, just off its cash flow.

WAITT: What year was that?

DUNCAN: February of ’86.

WAITT: And when did you buy the Baby Dolls in Fort Worth?

DUNCAN: August of ’87. Then Mike moved from Dallas and bought a ranch in East Texas. After two or three years, he missed the nightlife of the club business and I wanted to get in the country business. We had lunch one day and I said, “Mike, I want to open a country and western joint.” He said, “So do I.” I said, “Well, let’s do it.” We built the first Cowboys by White Rock Lake. We bought an old Winn Dixie grocery store and converted it.

WAITT: And how does Nick Mehmeti factor in?

DUNCAN: He was in the topless business in Dallas. He bought PT’s from Hal Lowrie. He lived in Chicago at the time. He was fairly young too, in his mid to late-twenties. He operated PT’s and he did a real good job, and he had a lot of the same ethics and philosophy that we did on how to make money. Just by coincidence, he officed at the same building that we did. We became friends. And when Cabaret Royale became available, I said, “Let’s partner up and buy this club.” We joined forces to buy Cabaret Royale. He kept all his stuff, I kept all my stuff and we owned Cabaret together. It wasn’t long after that we owned six or seven places together.

In 2000, the B&M Management chain had 13 adult nightclubs—Baby Dolls in Dallas, Fort Worth and Arlington; the Fare East and Fare West in Dallas; the Fare in Arlington; LaBare in Arlington; Deja Vu in Dallas; Michael’s International in Houston; PT’s in Dallas; Lipstick in Dallas; Cabaret Royale in Dallas; and the Million Dollar Saloon in Dallas. B&M’s portfolio also included John y Miguels restaurant in Terrell; Nick’s Sports Bar & Grill in The Colony; Nick’s Sports Restaurant and Bar in Rowlett; Rolling Meadows Restaurant in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin; Sports City Cafe in Mesquite; the Cowboys chain of country and western bars in Dallas, Arlington and Atlanta, Georgia; and a 3,700-plus acre cattle ranch, boasting 1,000 head of cattle in east Texas. Toss in consulting for the fashion industry, financial services and real estate, and you begin to get an idea of the scope of Duncan Burch and Nick Mehmeti’s business activities at that time.

WAITT: Are you and Nick still partners?

DUNCAN: Yes. Some real estate stuff.

WAITT: A third name Scott mentioned earlier was Bert Stair.

SCOTT: He’s a long-time employee who has been here since day one.

WAITT: Who are some other key people who have worked with your organization over the years and made a big impact? What about Kathie Golden? I remember for years if ED called Burch Management we had to go through Kathy to get you on the phone.

DUNCAN: Kathie was a gatekeeper. She was very key. She started with us a year or two after I got into the business. She was integral in taking care of many things for me. There have been three or four back-of-house office staff who have been key to helping me make it.

Originally, a guy named Steve Webb. He took care of our office and all the hiring and all the personnel and the human resources and the legal. So I didn’t have to worry about any of that. He did a great job on it. Bert Stair did all the operations of the clubs. And our brother-in-law worked with us also, Gene LeClaire; he was a CPA.

After Steve Webb, the guy who took his desk was Steve Craft. They took care of all the stuff I didn’t want to spend time on. It allowed me to spend time in the clubs, making it a fun atmosphere for the customers and the staff and the entertainers, and making the cash registers ring.

WAITT: While you’re buying the clubs and operating them, what’s happening in your personal lives in terms of wives, children, grandchildren?

SCOTT: Yes, yes, and yes. I have a couple of kids and a couple of grandkids. I was married for 30 years. I got divorced when I was 60, but we’re still very close.

DUNCAN: I got married young, about 18 or 19. My wife helped me clerically when I first bought Deja Vu. It wasn’t long after that I bought a Mexican restaurant in Terrell (Texas) and she started running it. And the next thing I knew, she was married to the restaurant and I was married to Baby Dolls. I had an apartment by the club. I wasn’t going home and she was working all the time. And I just realized that, she was a great wife and she didn’t need to be married to me. She needed to be married to somebody who was going to come home and wake up with her. The clubs just took over my life.

So we parted ways—and stayed married another 20 years—until she eventually found somebody and wanted to get married. She is wonderful. We are the best of friends. I have two children, although none with her, and two grandkids.

WAITT: The vast majority of adult nightclubs across the country are single-owner clubs. Your first business was the plumbing industry, but you made the decision to own more adult clubs after that first Deja Vu club. Why?

DUNCAN: The challenge. The fun.

WAITT: It’s interesting that you don’t say “to make money.”

DUNCAN: I’m sure that’s there, but it’s the challenge. The challenge and the fun of doing it. Building a team.

WAITT: Some founders I have interviewed said it was the thrill of making the deal.

DUNCAN: No, not for me.

WAITT: You had a smorgasbord of clubs, some small and blue collar, some large and white collar. And an assortment of different names for all of them. Was that diversity planned, or were you just buying what was available?

DUNCAN: It was planned because our first four or five clubs were all in the same shopping area. We were next-door or across the parking lot from each other. You could park in one parking spot and go to five or six clubs that we had. So we were competing with ourselves, right? We had to put a little different taste and a little different hook into each club.

WAITT: Some of the founders I have interviewed would open a club in one market and then start opening clubs in other markets so they could go national. Though you’ve owned numerous adult clubs, you’ve been content to stay in the Dallas, Fort Worth and Houston markets. Were you not interested in repeating your formula in markets outside Texas?

DUNCAN: We were interested. But we knew it was harder to operate out of town, so if we couldn’t find a location that we thought was perfect, we were going to pass. We did find markets and clubs that had pluses, but they also had negatives.

WAITT: The big chain operators focus on a brand name, like Spearmint Rhino or Deja Vu or Hustler, and use the same name on all their clubs. You owned a number of clubs but they all had different names for the most part. Why not go the branded club route?

DUNCAN: That was never our objective.

WAITT: There’s no question that you’ve been successful here. You’ve been able to succeed where other people who came into the market from out of town haven’t. Does it help being local, homegrown guys?

DUNCAN: I’m sure the fact that we’re here and all our clubs are right in our backyard certainly helps. But we could move to a market like Memphis and do the same thing. We could recreate it.

SCOTT: As close as Houston is to Dallas, it was a bear trying to get our club there turned around and going. You had to travel there; we had an apartment there. But Duncan built that thing by sitting in the club and being in the club every night.

WAITT: I remember your first club, Deja Vu. It was on an end cap in that shopping center. It was small, right?

DUNCAN: It was tiny. About the size of this room. I don’t know what the seating capacity was, but we crammed it in.

WAITT: It’s interesting that that tiny club was the catalyst to get you to the point where you owned giant clubs like Million Dollar Saloon and Cabaret Royale.

DUNCAN: Exactly. That’s the way it worked.

WAITT: Baby Dolls Saloon did huge numbers. It was often listed in the Top 10 list by the state in alcohol sales. The Dallas Observer once wrote, “Baby Dolls is Dallas’ top titty bar, literally: It sells more booze every month than any other joint in town.” Considering at one time there were more than 70 adult nightclubs in the Metroplex of Dallas-Fort Worth, why do you think Baby Dolls Saloon did such good business?

DUNCAN (smiling): Besides the ownership and our operating skill? Not to be boastful, but it was the way we ran the club. The way we treated the customers and the entertainers and the staff. We did business to do business again. We didn’t want to fight. We didn’t want to hurt anybody. We didn’t want to be egotistical to a dancer and say, “By God, we’re the boss, sugar.” We treated everybody special.

When we bought the place, we had eight day-shift girls and maybe 15 night-shift girls. In no time, we had 25 during the day and more than 40 at night. Eventually, we had over 100 at night, because we treated them right and we treated them special. We had customers coming back again and again because there was somebody to fall in love with.

We tried to get entertainers that fit everybody’s taste, not just our taste, because there’s an ass for every saddle. From big-boned girls to skinny-rail girls, we hired everybody.

“We tried to get entertainers that fit everybody’s taste, not just our taste, because there’s an ass for every saddle.”

—Duncan

WAITT: It’s interesting that your philosophy was to treat the entertainers and the staff just as special as the customers.

WAITT: It’s interesting that your philosophy was to treat the entertainers and the staff just as special as the customers.

DUNCAN: Hell, yes. We wanted the employee base fighting for us and caring about us because we cared about them. We wanted the bartenders to put the money in the register, not in their tip jar. And then we wanted to reward them. We’d do fun things for them. We’d take them on trips. We’d do things that they hadn’t done before.

SCOTT: We took all of the management and a large portion of the bar staff to Cancun. Had to do it in three trips because there were so many of them. And we did those trips numerous times. We’d go to Mexico, to Las Vegas.

WAITT: Baby Dolls Saloon gets all the love, but another of your clubs, The Fare, never received the same amount of attention, even though it was a big earner and was also successful.

DUNCAN: Very successful. It did well on Greenville with the SMU (Southern Methodist University) college crowd, Now, when we left Greenville, after the city zoned us out, we put The Fare name up at a couple of places and it didn’t do as well. We didn’t ever replicate it.

WAITT: That speaks to the importance of location.

DUNCAN: Yes.

The early history of the Dallas stripclub industry could have filled an entire season of the popular network TV soap opera at that time called, “Dallas.” It ran from 1978 to 1991, and it’s 1980 “Who shot J.R.?” episode remains the second highest rated prime time telecast ever.

The series was full of legal battles and suspicious deaths.

As was the Dallas stripclub scene back then.

In 1968, Don Furrh was the first kingpin of stripclubs in Dallas/Fort Worth, owning 18 mostly blue collar joints on Harry Hines Boulevard and Industrial Boulevard. He eventually sold all his clubs, went away for three years, and then came back to Dallas to open the Million Dollar Saloon in 1981, billed at the time by the local media as the first upscale topless club in Dallas. It was soon the highest grossing stripclub in town. But in 1988, Furrh was found shot to death in his home. The case remains unsolved.

Two years after the Million Dollar opened, oil tycoon Salah Izzedin and some partners opened Rick’s Cabaret in Houston, the first high-end, white collar club in that city. Everything was hunky-dory until the partners started infighting and everyone ended up spending more time in court than in the club.

Izzedin moved on to Dallas and dropped $8 million to build Cabaret Royale in 1988, surpassing the Million Dollar Saloon as the top dog in the market. It had a roster of over 400 entertainers, $1,500 annual memberships and was featured on “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.” It was truly a showpiece, but was soon plagued by financial and legal woes leading to a bankruptcy filing for two of its corporations.

Next came a ruling by the US Department of Labor that the club owed $11 million in back wages to its entertainers in one of the first volleys in the never-ending employee-versus-independent-contractor debate. There were also some age discrimination lawsuits. Along the way, the club’s auditor, two weeks before the club was to turn over its financial records in bankruptcy court, was found dead with a gunshot wound to the head in the club management offices. The death was ruled a suicide.

WAITT: Aren’t you happy that you acquired those huge clubs—the Million Dollar Saloon and Cabaret Royale—after all the strife was over?

DUNCAN: Well, yeah.

Meanwhile, the Burch’s other big money-maker, Baby Dolls Saloon on Northwest Highway, was under attack by the city at the urging of a very vocal and very persistent neighborhood association, the Bachman/Northwest Highway Community Organization. The association came after the club, even though the Burches were functioning as good neighbors.

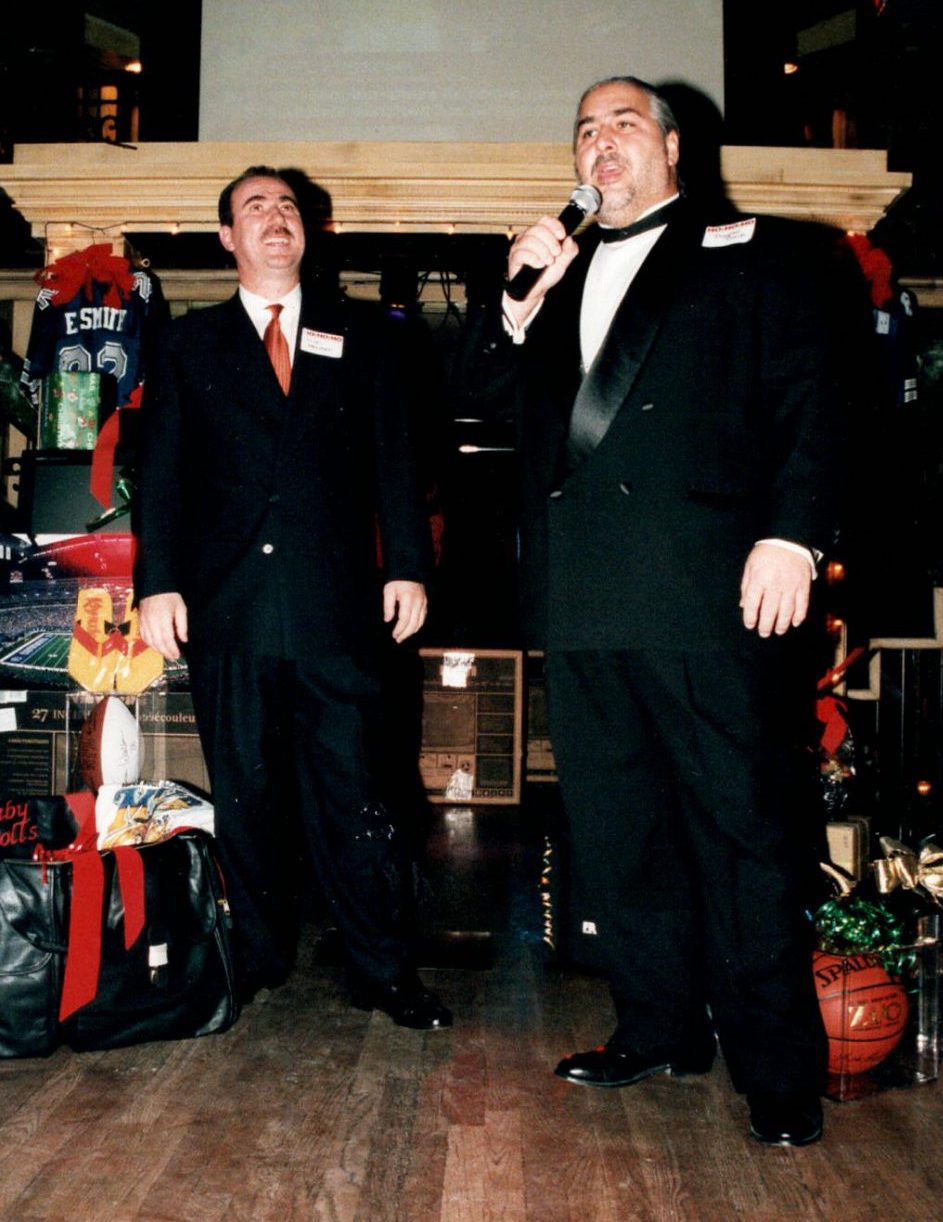

In December 1992, they picked up the $10,000 tab to keep an annual Christmas party in Bachman Lake Park going; the city was going to cancel the event for lack of funds. The Burches sent their dancers to the event, dressed in cuddly stuffed animal costumes rather than bikinis and pasties, to distribute goodies in the park. Burch’s largesse also helped the public schools in the Northwest Highway neighborhood, including Stephen C. Foster Elementary and Obadiah Knight Elementary; they supplied the schools with playground equipment and encyclopedias. “We operate as a caring, concerned, and contributing corporation,” said the Burches in a statement.

But still, the neighborhood association came after the club.

DUNCAN: The city trying to put Baby Dolls out of business actually helped our cash registers. They were setting up in the parking lot and putting us on the news every night. You can’t pay for that advertising. We would be on at five o’clock and at 10 o’clock.

The neighborhood association was hell-bent on a mission to close Baby Dolls down. And they were tenacious. They did not give up. They were a bulldog and they grabbed hold and they hung on for years. That’s ultimately why we relocated. They were so vicious about it. They called the press. They called the city attorney. They called every council person. They had neighborhood meetings and rallies and picketed out front.

SCOTT: They got the press there and said that we’re going out of business and we won’t be here for much longer. So people showed up just because they wanted to see the club before we closed.

DUNCAN: And if we got them in there once, then we got them for good. The atmosphere was so good and fun that they kept coming back.

SCOTT: I’d go to those neighborhood association meetings, and stand right up and just let them throw bottles at me, or whatever. Most of them didn’t give a rat’s ass (about adult clubs), but there were always two or three people complaining. They’d find condoms in a park two miles away and the club would get blamed for it.

DUNCAN: That was Scott’s biggest role for the company. He spent almost all of his time doing public relations and political work for us. He played a major role in the Dallas political scene, and he was in Austin for every state legislative session. He worked with the Dallas City Council, the neighborhood associations, the Convention and Tourism Bureau for us.

WAITT: Without the aid of social media back then.

DUNCAN: He didn’t have any of that. He had to do it 100 percent in-person. And he got along with the people. He made them like him. He’s a likable guy. So that was his biggest asset to our company, which was a great help because we had so much gunfire coming our way.

WAITT: Have all of your adult clubs been topless with alcohol? If so, why weren’t you interested in opening nude, no-alcohol clubs?

DUNCAN: We had some BYOB places.

WAITT: Which did you prefer?

DUNCAN: Alcohol places. They come with a lot more scrutiny, yes, but they also make a lot more money.

WAITT: You have owned both blue collar clubs and high-end white collar clubs. What are the pluses and minuses between the two?

DUNCAN: With blue collar clubs there are so many more customers. The customer base is so much bigger to work with because even the white collar people will come to the blue collar club. When they have their customer from out of town or they’re trying to get a $2 million order from Texas Instruments, they’re going to take them to The Men’s Club or The Lodge. But when that guy goes out by himself tomorrow night, he’s coming to Baby Dolls. It seems like the white collar guys, a lot of them, they go away. But with blue collar, you’re still seeing the same guy 17 years later. And with the white collar club, the customers are so much more demanding and there are so fewer of them available as customers.

WAITT: What’s different about Texas customers and Texas entertainers compared to other markets?

SCOTT: I don’t know that there is any difference, really. For us, it’s just promoting fun. We want you to come in and have fun. Not necessarily fall in love with Cindy or Shirley, although that happens. We don’t want, as Duncan always says, the customer waking up the next morning thinking, “Oh my God, what have I done? How do I pay for this?” We want that guy to come in and spend a few dollars and come again tomorrow night.

WAITT: But when you’ve been in other markets and clubs, have you noticed anything different?

DUNCAN: I’m sure we have, but nothing stands out.

WAITT: When the first huge, high-dollar, white collar “gentlemen’s clubs” started coming out, everyone wanted to own a fancy club with valet parking and fine dining. Do you think operators lost sight of how profitable smaller, everyman stripclubs could also be?

DUNCAN: Absolutely.

WAITT: Why do you think so many people wanted a big, high-end club?

DUNCAN: Their ego.

“We don’t want the customer waking up the next morning thinking, ‘Oh my God, what have I done? How am I going to pay for this?’”

—Scott

WAITT: Your small Deja Vu club is a testament to that. You built an empire off of a 60-seat everyman’s club.

WAITT: Your small Deja Vu club is a testament to that. You built an empire off of a 60-seat everyman’s club.

DUNCAN: Yes.

SCOTT: And Baby Dolls was just a larger version of that club.

WAITT: How do you think entertainers have changed over the years in terms of looks, temperament, attitude and their expectations?

DUNCAN: I don’t think they’re any different.

WAITT: What about social media and cell phones?

SCOTT: Their lifestyle might be different. And the way they communicate. But I don’t think the girls are different.

WAITT: I am asking all of the founders I interview for this series four questions. The first is, what is the biggest mistake first-time club owners make?

DUNCAN: Chasing girls. That’s probably what sunk many of them. Then that turned into drugs. I think that’s why we got to buy a lot of clubs over the years because the owners went down behind drugs and gals.

WAITT: What is the biggest mistake club owners who have owned a club for more than 10 years make? The most common answer is they don’t go to their club anymore.

DUNCAN: Yes. The other day I was at dinner with a club owner and he complained that the club across the street was running these big numbers which is why his club was suffering. I said, “No, it’s not. It’s because you won’t go to your club anymore. You don’t want to show up there. That’s why.” And he said, “You’re absolutely right.”

Many owners don’t go to their clubs after 10 years, and for some of them, it doesn’t even take 10 years. Two or three years of that cash flow and they get blinders on that it’s automatic, right? I sold my clubs a year ago (more on that later). But if I’m in town, I’m at Baby Dolls. I still want to make sure that it’s successful. I want to make sure the club rocks.

WAITT: Who is the most important staff person at a club and why?

DUNCAN: You certainly got to have management there, but I think it’s the entertainer.

WAITT: Who is the most expendable staffer at a club and why? Some people have said the DJ.

SCOTT: The DJ plays a big part. He’s huge. He’s right behind the dancer. He’s number two, maybe even number one.

WAITT: How many entertainer employee/contractor lawsuits have been filed against you, and how did those turn out?

DUNCAN: Very, very few.

WAITT: In the 2000 ED Magazine cover story, Duncan, you said, “We are very hands-on. We are definitely in our stores. For years, we went to every club every single day. We have now built tiers into our management structure so that a lot of what we used to do personally is done by our management team, but we are still out on the streets seven days a week.”

Did you maintain that kind of presence over the next 20 years?

DUNCAN: I didn’t. I kind of dropped going to Houston. I kind of dropped going to even Fort Worth and Tarrant County on a regular basis. I went to Baby Dolls, but I let the other ones become stepchildren. And really, at that point, I felt like Bert (Stair) could do it. I just let him work and do his job out there. And I had confidence in him.

“If you keep it fun, if you keep the party going, and if the employees are excited, then the customer is going to come.”

—Duncan

WAITT: In the 2000 cover story you also said you rotated your managers from club to club two to three times a year, saying “Our philosophy is a new broom sweeps the cleanest. Rotating keeps them from getting stagnant. It gives them new challenges.” Did you continue doing that over the next two decades?

WAITT: In the 2000 cover story you also said you rotated your managers from club to club two to three times a year, saying “Our philosophy is a new broom sweeps the cleanest. Rotating keeps them from getting stagnant. It gives them new challenges.” Did you continue doing that over the next two decades?

DUNCAN: We did to a degree. But as we shrank, we didn’t have as many clubs to rotate. And then we got into the Latin club business and had to have bilingual staff. So that made rotating harder. But, yes, we continued to try to do that.

SCOTT: We want the trained, developed guy going in to four new walls with fresh eyes.

DUNCAN: You see things that the last manager missed in the club that they’ve been showing up to for the last six months. You’ll walk in and see that there’s a box of candy on the floor behind the door girl. That ought to be in the cabinet or hidden. But hell, in your club, that box of candy was there every day. You just got used to seeing it there.

WAITT: Also in the 2000 interview, Mehmeti said something that most of the recent interviewees from the ED Founders Interview Series have echoed. He said, “Owners cannot sit on their laurels. They have to move up the scale. They have to make their clubs nicer, do some renovating, add some lighting, enlarge their building and add in food sales. They have to make their clubs more inviting.” Twenty years later that advice seems even more timely now.

DUNCAN: That’s one way to approach it. But if you keep the atmosphere right, if you keep it fun, if you keep the party going, if you keep the excitement and if the employees are excited, then the customer is going to come. I don’t care if it’s a dump. If you do that, then you don’t have to do the other. But if you do ‘em both, it’s going to be just more icing on the cake.

WAITT: In the late 1970s to early 1990s, there was no cooler and hipper market than Dallas-Fort Worth. You had Roger Staubach, Tony Dorsett and Tom Landry with the Dallas Cowboys. No to mention, the incredibly sexy midriff-baring Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. You had rocket-arm Nolan Ryan and the Texas Rangers. You had the “Urban Cowboy” movie and massive honky-tonks like Gilley’s and Billy Bob’s Texas on the big screen, and the network soap opera “Dallas” with the feuding Ewing family on the small screen. The oil business was on fire, as was the commuter and telecom technology boom. And Dallas, with all its disco-era single bars, was a magnet for every hot gal and guy in the country. Do you ever look back and go, ‘Man, that was the perfect time for us to get into this industry?’

SCOTT: No, I don’t. Maybe those things had a lot to do with it and we don’t realize it because we grew up here. It was just what it was. Tom Landry lived six blocks away. We went to school with his kids.

WAITT: Dallas-Fort Worth has always been a very competitive market with a number of top-notch clubs, all of which have been recognized with ED Annual Awards. Clubs like The Lodge, The Men’s Club, Rick’s Cabaret, Spearmint Rhino, Bucks Cabaret, Silver City Cabaret, and from the past, The Clubhouse and Fantasy Ranch in Arlington. That said, I’ve always been impressed with the camaraderie between all of you, compared to other markets where there is a lot of animosity among competing club operators. Is it just good ol’ Southern hospitality?

DUNCAN: I don’t know if there are a little bit less egos that happen to be in the industry here. We were just wise that we needed to work together. It made sense. We all understood that we were fighting the city together.

“I don’t know if there are a little bit less egos in the industry here (in Dallas). We were just wise that we needed to work together.”

—Duncan

WAITT: But you all also seem to be personal friends.

WAITT: But you all also seem to be personal friends.

SCOTT: We are.

WAITT: I have been going to stripclubs since I was 16, which is 51 years ago, and I have visited clubs from coast to coast. I think the most beautiful entertainers I ever saw during that time were in the Dallas clubs in the 1980s and 1990s. Why did Dallas attract so many knockout dancers?

DUNCAN: I don’t know the answer. I do know when I sold Baby Dolls to Rick’s, I was sitting in the club with Eric (Langan, RCI president), and he commented on how bright the lights were in the club. He said, “I never thought we’d own a club where the dancers look good enough that we could turn the lights up this high.”

WAITT: This year’s 2024 Gentlemen’s Club EXPO will be in Dallas, and you have put out the welcome mat for us, including meeting with ED Publisher Dave Manack to discuss ideas for the convention and also offering your gigantic Cowboys Red River Dancehall and Saloon for the Opening Night Party and an after-party at Baby Dolls Saloon. Why is it important to get involved?

DUNCAN: Because it’s our industry friends and the industry that has been our life for the last 40 years. So when they come to your hometown, you throw out the welcome mat.

WAITT: Duncan, you certainly don’t fit the public’s preconceived notion of what a strip club mogul should look like. Were you always like that?

DUNCAN: Probably. We are who we are.

WAITT: But when you meet people, are they ever surprised at what you do?

DUNCAN: Oh, I think so.

At Baby Dolls you hear a constant refrain of “Hi Duncan” and “Hi Scott” from staffers, entertainers and even customers as they walk through the club. Everybody knows the brothers and everybody is cheerful to them. Duncan gives me a tour of the large, two-level club. Backstage, the dressing room is gigantic and immaculately modern and clean. There are over 150 lockers, 40-foot-long mirrors, a walk-in shower that could hold six entertainers and several boutiques selling dancewear.

“We like to make it nice for the girls,” says Duncan. There are large signs everywhere proclaiming, “If management or anyone requests a tip, fee or any form of payment to be hired or to be allowed to work here, please notify your DC/GM immediately. This company does not and will not tolerate management demanding, threatening or extorting money from individuals.”

As we continue the tour, Duncan stops two different times to scoot a chair that someone left out too far from the cocktail table when they left. The club has a manager, and plenty of floor men, waitresses and bar backs, but Duncan isn’t going to wait. When he’s in the club, everything needs to be perfect.

We sit at the huge round, open bar on the main floor, and order beers. An older woman comes over, drapes her arm over Scott’s shoulder and then Duncan’s. I hear her reminiscing and telling stories. Both brothers smile and listen patiently. When she leaves, Duncan says, “She used to be a dancer and then a bartender and now she just kind of hangs out. We inherited her when we bought the club.” You can tell the brothers have heard her stories and forced familiarity many times, but they treat her kindly. It’s just their nature.

Scott points to a large tip jar on the bar. It’s filled with $2 bills. When was the last time you saw a $2 bill? “We’ve always had the waitresses and bartenders give change back to the customers in $2 bills,” says Scott. “A guy will tip $2 as fast as he will tip $1. And now we’ve doubled their tips.”

A 12-inch wide strip of metal is in the middle of the bar top and circles around the entire bar like a racetrack. It’s supposed to get freezing cold so you can set your cocktail or beer on it. It’s not working. And Duncan isn’t happy about it. He calls the manager over and they discuss the ETA on when replacements parts are arriving.

I’m shocked, and pleased, to hear the DJ play an AC/DC song, and mention my surprise to Duncan, who says,“We play rock music that all the customers know, and every third song has to be a country song. No rap, no hiphop, no electronic dance music. Never.”

“We wanted to run our joints the way we wanted to, without any extra scrutiny that we didn’t already get from being in this particular industry.”

—Duncan

WAITT: In 2003, you both received ED’s Innovator of the Year Award at that year’s EXPO Awards Show. Back then, you were more involved in the industry, with ED Publications, with the Annual EXPO and even with ACE National, of which Scott was the President from 2003 to 2005. It seemed like at that point you were interested in going the route of some of the other operators who build their profile and their chain. But then you kind of faded back into the woodwork at least from an industry exposure standpoint. Why was that?

DUNCAN: I don’t know that I know the exact answer to that, but at that time we had bought Million Dollar Saloon as a public company. It was just a pink sheet trading company. And we thought that we wanted to put everything into that public company and go that route. And it wasn’t long after dealing with the SEC and all the filings and all the reports you got to do and the “I’s” you got to dot, and the expense of the certified audits, that we quickly soured on making the public company bigger and going that route.

It just didn’t fit our personalities. Yes, that’s a way to get an exit strategy and probably get top dollar, but that wasn’t on our mind, an exit strategy. We just wanted to run our joints and we wanted to run them the way we wanted to, and without any extra scrutiny that we didn’t already get from just being in this particular business. We didn’t want the SEC and their rules, too.

WAITT: Scott, you have been the primary spokesman and goodwill ambassador for the company. What is the secret to keeping good relations with city officials, the police and the community?

SCOTT: Being who you are. Just letting them see you’re a real person. That you’re an everyday person who reads the newspaper. Has kids that go to school. Let them know that you’re not a B-rated movie caricature.

WAITT: Talk to me about the Texas Entertainment Association, which is a statewide association for adult nightclubs. TEA was started long before ACE, probably before any other statewide adult club association. Were you one of the founders?

SCOTT: We were through Steve Webb, which would be us, and with David Fairchild (of The Men’s Club).

WAITT: Was is just Dallas or other cities in Texas?

SCOTT: It was the four big players—Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, Austin and San Antonio—and smaller markets like Laredo, Wichita Falls and Amarillo.

WAITT: When I talk to other club owners in states that don’t have a statewide, they say can’t convince other club owners to get involved. How have you been successful?

SCOTT: Because of the constant legislation that is fired at us. For dues, we use bar sales. Everybody pays five percent of their January sales with a cap of $25,000. So, there’s probably six of us that pay that cap. And then the rest of them just pay something. We try to make it equal.

WAITT: The Dallas City Council passed ordinances in 1986, 1993 and 1997 to rein in sexually-oriented businesses. The Dallas Observer wrote that Dallas clubs are “tireless champions of the First Amendment, ingenious loophole locators and ceaseless circumventers of zoning restrictions … SOBs have plenty of cash to keep the legal process going through endless appeals and legalistic permutations. Meanwhile, the clubs will stay open.”

Back then you also served 24 city officials, activists and former city workers with subpoenas, ordering them to provide testimony for a possible lawsuit. Your lawsuit was going to allege that you “had been denied fair hearings and due process claims” in 14 instances before police, zoning and other regulatory boards in recent years. Did you get their attention when you turned the tables and put them on the legal hot seat?

SCOTT: They probably were surprised, yeah.

“Just letting them (critics) see that you are a real person, an everyday person who reads the newspaper, who has kids that go to school.”

—Scott

WAITT: I’ve always thought the industry should be more proactive and start filing class-action suits on the basis of discrimination against all things adult.

WAITT: I’ve always thought the industry should be more proactive and start filing class-action suits on the basis of discrimination against all things adult.

SCOTT: They are targeting us, which is unfair.

WAITT: There is no question that the big four—Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio and Austin—have benefited from being top convention/tradeshow destinations, just as there is no question that having adult nightclubs in those cities have made them appealing location sites for the meeting planners of those shows. That said, why have Dallas clubs had to fight so much city and state legislation designed to shut them down? It’s been nonstop for decades. Why do you think these bureaucrats keep attacking?

SCOTT: We’re an easy target. It’s something for them to talk vocally about. The city, luckily, hasn’t been too bad over the past 20 years. It’s the state. The state’s the bad one.

Last year Duncan sold his five remaining adult clubs—the two Baby Dolls Saloons in Dallas and Fort Worth and three Chicas Locas clubs in Dallas, Arlington and Houston—to Rick’s Cabaret, (RCI International) for $66.5 million. I ask Duncan why he decided to sell then. He said that Rick’s had approached him numerous times over the past 15 years, and when they called last year, he decided, “It was time.” He knew he wanted get paid out at some time, and as he hit his mid-60s, that time seemed to be now. In the past, he said, when he passed on an offer from someone to buy one of his clubs, and 10 years would go by, he would realize that he had made as much money over those 10 years as he would have had he sold, but he would still own the clubs.

“Ten years from now, I may be thinking the same thing, but oh well,” he says.

WAITT: You are still involved with the adult clubs as advisors to RCI. What does that entail and how long do you see that happening? Are you a consultant?

DUNCAN: I’m not sure what I am.

WAITT: Did most of your key people stay?

DUNCAN: Yes. That’s the reason I have stayed on. I committed to our folks that I would stay on. And once Rick’s realized that I was still operating it, just like I was an owner-operator, and that I had one thought in mind, which is maximizing the net profit, they left me alone and let me pretty much run it the way I was prior to the sale.

WAITT: When did you acquire the Chicas Locas hispanic clubs?

DUNCAN: The first Chicas Locas had been the Million Dollar Saloon 2 (the original Million Dollar Saloon had been zoned out). It eventually was revived at Cabaret Royale. We had a male strip joint La Bare that became Chicas Locas Arlington, and when that got zoned out we moved it to what had been Lace. And the third one in Houston used to be Michael’s International.

WAITT: Why the switch to a Latin/Hispanic format?

DUNCAN: We thought Texas was like South Florida. Latins were key players. They work, they drink, they party. They earn a salary and they have expendable income. There was an opportunity and there wasn’t anything going on like that.

WAITT: And were you right?

DUNCAN: Absolutely. It was a home run. The first location was off the charts for us.

“The customer base for regular nightclubs is more fickle. They always go for that new club or the remodeled club with the reformat.”

—Duncan

WAITT: When it came to the entertainers, did you have to get Latin entertainers or did you do a mix?

WAITT: When it came to the entertainers, did you have to get Latin entertainers or did you do a mix?

DUNCAN: In the beginning, we kept the same girls, and just changed the name and the music, until it just filtered on its own.

SCOTT: Now any new-hire for waitress, bartender or manager has to be bilingual so they can serve both customer bases.

DUNCAN: How does the customer base compare to other non-hispanic clubs?

SCOTT: It’s good, but there does seem to be a little more trouble in those clubs. You know, hot-blooded Latins.

DUNCAN: It’s the females as much as the males. Some of the Latin women can get extremely jealous. And they can have a little hotter temper.

WAITT: Comparing adult nightclubs and regular nightclubs, what have been the pros and cons of each?

DUNCAN: The customer base for regular nightclubs is more fickle. They always go for that new club or the remodeled club with the new signs up and a reformat. There’s always one opening and that’s where the people flock to. We’ve been very blessed to maintain an upward trend in sales increasing at Red River for 27 years here. It’s unusual for a dance club to hang in as long as we’ve made it work.

WAITT: What was your typical workday like when you had the adult clubs?

SCOTT: I’d go to the office about 6 am and go through the mail and vouchers from the clubs from the night before. Just general stuff like that. I would go around and fill ATMs also. So I might be in the office for three hours and go out for an hour and then back to the office. Until 5 pm. For me, it was an 8 to 5 deal.

DUNCAN: My work day would be mostly at night. But in the beginning, it was a lot of daytimes. I tried to be there at opening a few days a week in the beginning. In the last few years, it hadn’t been the case. And I was there for closing pretty much every day. Once I get there, I stay there all day. If I open, I close. If I get there at three or four in the afternoon, I close.

WAITT: Would you go by all the clubs?

DUNCAN: For many years, yes. Every club, every day.

WAITT: Were the GMs happy to see you walk in or were they nervous?

DUNCAN: A little of both. Some were happy and some hated it. You know, the ones who were doing a good job and not scamming or cheating, they wanted to see you.

WAITT: You have been immersed in this industry for four decades. As we enter 2024, what are the biggest changes in adult nightclub ownership and operation—both good and bad—that you have seen over the years? For me, one of the biggest changes would be the white collar clubs with valet parking and in-club dining.

DUNCAN: Well, what you just mentioned, obviously. The facilities going from little hole-in-the-wall, one-stage biker joints to really mainstream clubs in many cities. If you walk into some of the strip joints now, there’s nobody staring at the stage or gawking. They’re watching sports on dozens of TVs. They’re talking to their buddies. They’re shooting pool. It isn’t just about the strippers. It’s become mainstream.

SCOTT: There are also a lot of dates and a lot of couples coming into the clubs now.

WAITT: If you could go back in time four decades, what is the one piece of advice you would give your younger self?

DUNCAN: I don’t know if I’d do anything any different.

SCOTT: I would say put more money in the bank than I did over the 40 years.

WAITT: Is the adult club industry still exciting for you?

DUNCAN: I like what we do. It’s still interesting.

SCOTT: It’s fun. You hang around a bunch of young people. It keeps you young.

“It’s fun. You hang around a bunch of young

people. It keeps you young.”

—Scott

“I like what we do. It’s still interesting.”

—Duncan

WAITT: When not working, what do you like to do for fun or relaxation? Any interesting hobbies?

WAITT: When not working, what do you like to do for fun or relaxation? Any interesting hobbies?

SCOTT: Mine is golf, but it’s slowed down.

DUNCAN: For me, it’s work. Just the clubs.

WAITT: But didn’t you used to be a big player in Vegas?

DUNCAN: I like to travel. Not just to Vegas. I like to see different things around the world. Different cultures and their architecture, and meeting new people.

WAITT: Last question. For the record, who did your parents like the best?

SCOTT: I don’t think they had a favorite. We had great parents.

DUNCAN: We did. They’re both deceased, but they were great to us. And we tried to be great to them in the later years, too.

* * *

NEXT ISSUE: The Founders Interview with a man who truly needs no introduction: industry veteran Jim St. John.