Like many musicians before him — and inevitably like those that will come after — Mike’s Dead was living in Los Angeles, broke — sharing a two-bedroom apartment with five people.

“I was super broke,” recalls Mike’s Dead, who at the time in 2018 was producing music and working a part-time job on the heels of finishing audio engineering school.

“A buddy I lived with at the time, I would walk around freestyling, he was like ‘You have a dope, baritone voice. You could really do some rap stuff.’ I have a little background on that stuff but not a lot. He pushed me into that realm. That’s what started the whole thing. I had like 20 songs before I came up with Mike’s Dead and actually started fresh. We don’t keep in contact anymore but that was the foundation of this project.”

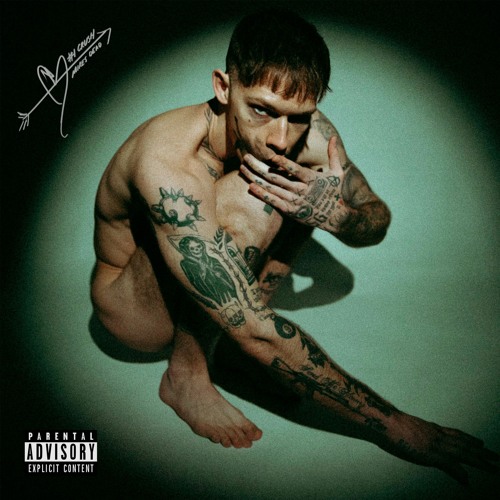

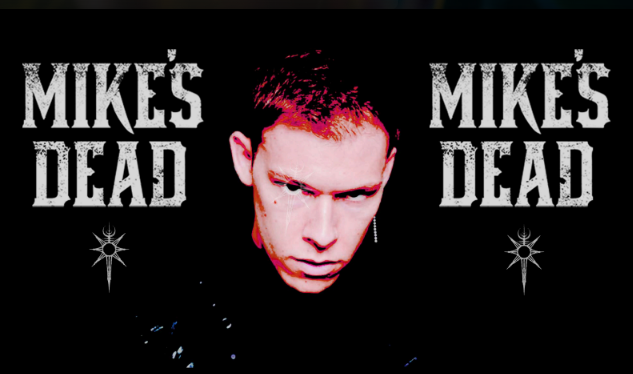

ED Magazine spoke with Mike’s Dead, courtesy of Bob Chiappardi and StripJointsMusic.com, about how audio engineering influences his musical consumption and identity, becoming a morning person and his single “#1 Crush.”

ED: You’re making beats for rappers and you’re freestyling around the house, what did you have to learn about the business side of music before Mike’s Dead launched in 2018? Was there any part of you that thought you were making a mistake or that maybe you were more suited to audio production/engineering?

MD: I got a little bit of background when I went to school. We had a music business program, so I was learning what PROs (Performing Rights Organizations) were, splits, the general overseeing background of understanding what sync licensing was and so on. Granted, I didn’t have real industry experience. As a 21 or 22-year-old kid, I was pretty ignorant to how things actually work. I’ve just been learning year after year.

I think I’m naturally a producer first. I’ve been doing it longer. You can play a single note from a glockenspiel (bells) and my brain starts pinging ‘We should take it this way.’ That’s how my brain works. I will say that’s a strong suit of mine. The artist side is a different strong side. It’s just two different concepts to me.

(Learning stage presence) has been relatively easier for me. If I was going to be a producer — and I was working with other people when I was starting to produce, rappers and pop writers — I have a certain skillset and certain mind that can’t deviate too far outside of that spectrum. As a producer, if someone sits you down and says I need a top 40 pop record, I’m not the guy for it. That’s what I started learning — I love synths, I’m an absolute nerd for sound design. I can’t even write in a major key. I started to realize I have a certain brain and it has to go a certain way. That’s been really beneficial to the artist side because it’s just me, I have control of all of it.

ED: Speaking of, you have a degree in audio engineering/production — how has that influenced not only how you create music but how you consume it?

MD: It makes you a snob. I think the second your ears get trained to understand what a good mix and a bad mix is, you start becoming a little jaded. Every artist at the end of the day is still a fan of music. I grew up on Linkin Park, New York hip hop, stuff like that. No matter what I’m listening to, I’m determining if I’m a fan of it or not, not from the standards of ‘Is this hitting at whatever RMS (root mean square)’ or loudness. When I get asked technical questions, I can turn that antenna on and start being like ‘the snare could come up.’

ED: Can you describe how you create “controlled chaos”?

MD: I think in the metal world, there’s a stigma for people that don’t listen to rock or metal, that it is a certain type of way. I think it’s funny — a lot of what I make is more industrial metal, industrial hip hop. Say I meet a doctor and I tell them I make industrial metal, they think Will Ramos from Lorna Shore (an American deathcore band). I think everyone has this stigma that metal sounds like this. I explain Nine Inch Nails is industrial metal, Marilyn Manson is industrial metal. What I see in the metal lane is a lot of it is chaos. I think the controlled chaos is being able to write the music to make it palpable and marketable. Manson and Trent (Reznor, of Nine Inch Nails) notoriously wrote with pop writers. A lot of rock is pop at the end of the day. Making sure it’s heavy enough, weird enough, it’s a little off-kilt, detuned and it’s gross but it’s also palpable and understandable to the common listener. That’s what I want things to sound like — as long as it maintains that integrity.

ED: I read you like to work on music first thing in the morning because it’s when you feel most creative — what’s the best thing you’ve come up with in the morning? How long has that been going on, have you always been a morning guy?

MD: Long story short, no. I think everyone in their early 20s stays up until 2, 3 in the morning and stays out late as hell. I used to work in the nightlife industry for a few years, I was working until 4, 5 in the morning. It definitely was not always like that. I started noticing that I’d wake up, skip breakfast, coffee, caffeine, I’m just rolling in the morning. I wouldn’t say I have a specific answer for what my best work was in the morning because I write all the time. That being said, now as I’ve gotten older, I have it down to a routine. I’m up at 6 am every day. When I tell other artists that, they’re like ‘What?!’

“I think the second your ears get trained to understand what a good mix and a bad mix is, you start becoming a little jaded. Every artist at the end of the day is still a fan of music.” — Mike’s Dead

ED: What’s the most humbled you’ve been meeting a fellow musician — can you talk about how that interaction went?

MD: A lot of my idols are dead, unfortunately. Chester Bennington (deceased lead vocalist of Linkin Park) was my No. 1 — that crushed me when that happened. When we played Aftershock Festival, I met Chris Motionless after the show. He’s a really great dude. I don’t put a lot of emphasis on people in general, no matter how big you are as an artist, I treat everyone kind of the same — we’re all humans. That’s how I address people in general, whether it’s fans or a massive artist, I always try to remain true to that. It was just a really cool conversation, shooting the shit. (Chris) is definitely someone I look up to in the industry.

ED: What’s your best gentlemen’s club story?

MD: I do have one. I’ve only been to a few gentlemen’s clubs. A bunch of buddies and I were in Scottsdale (Arizona) and we were out all night. The Uber had coupons for a gentlemen’s club and we decided to go. We didn’t want to spend any money. We get in, they take us to the back and tell us about the packages and dances available. All of us are drunk and don’t want to spend money. Twenty or 30 minutes go by and we’re sitting there and these two girls come up and start talking to us and take us to the back. I remember going back there and thinking ‘Why are we going back a second time, this isn’t going to convince us.’ The house mom comes in and is pitching us. My buddy doesn’t realize where we are and he just asks ‘Y’all got food?’ after this long spiel. So, we decide we’ll get these dances but only if we get eggs.

ED: StripJoints services DJs at gentlemen’s clubs nationwide, so, in your words, why would “#1 Crush” be a good choice to play at a gentlemen’s club?

MD: I think there’s this dark, provocative aggression in this song that’s a lot different from the original and that was my intention. I wanted to make it more intense, more in-your-face. I hope that’s something dancers can resonate with. It is the same tempo, it’s got the same groove, that nice pocket but it’s just got this intensity and aggression to it that kind of really sucks you in once you start really getting into the song and listening to how the tension flows throughout.